Excerpt from an article photographed and written for National Geographic:

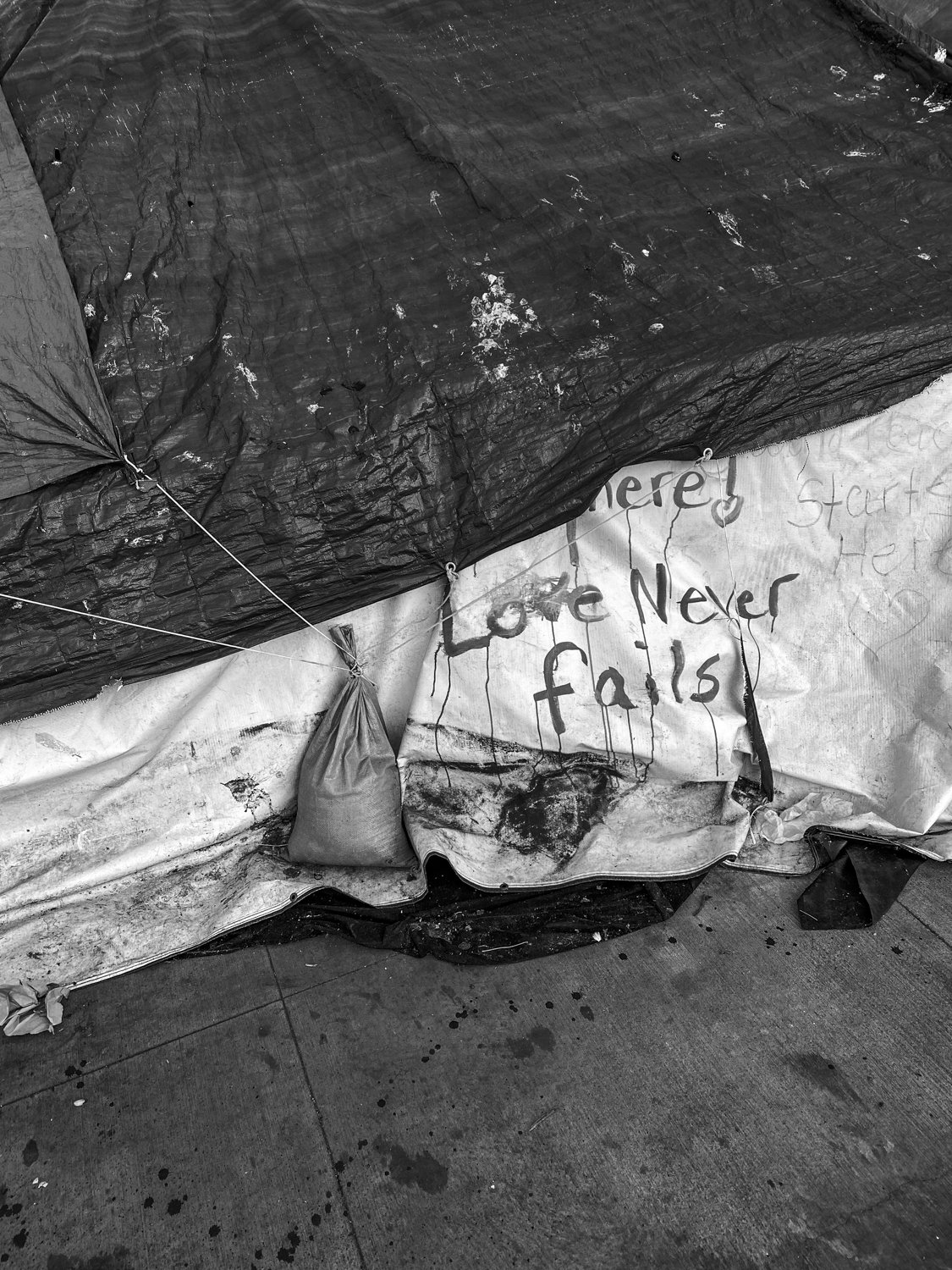

This city’s Skid Row has been home to people on the margins of society for more than a century. It’s a roughly 50-block area east of downtown, mostly warehouses, low-income housing, single-room occupancy hotels—and tents. The name Skid Row originated in Seattle, an hour south of the Washington farming region where I grew up. It initially described the logging communities along the “skid roads” where logs were dragged to be loaded onto ships at the port. Only later, around the time of the Great Depression, did it become synonymous with impoverished neighborhoods across the country. With some 5,000 people, L.A.’s Skid Row is like a little city within the metropolis—a city defined by the tents on its sidewalks.

During the 1970s, Los Angeles deinstitutionalized many psychiatric hospitals, discharging people from long-term facilities and sending them to clinics and halfway houses or simply abandoning them, a problem that persists. Around the same time, numbers of returning Vietnam War veterans hobbled by mental illness and drug dependence, also converged on Skid Row. For many in the community, missions and volunteer organizations are keystones, their only means of survival.

I’ve spent the past few months photographing, recording interview and audio of Skid Row and its residents—some of the most vulnerable people in our city. Life here is very hands on, very close. People live crammed together and are always mingling. They swap or share food, drink, drugs, alcohol, money. They stand shoulder to shoulder in lines to receive food and other donated goods.

I often feel drawn to photograph people who live on the hard margins of society. I became interested in Skid Row after moving to L.A. a few years ago. Before then, I’d spent most of my time covering conflict-related stories outside the U.S.—in central and northern Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East. Then, with the birth of my daughter, Poppy, I began limiting my time away from home.

When I first drove through the neighborhood, I was amazed by all the tents and the people crowding the streets. Skid Row had a raw energy that felt more like the Democratic Republic of Congo than America, but it took awhile before I was ready to photograph there. I first needed to tackle my own PTSD from my previous work in order to connect with the people on Skid Row and understand the destructive forces that had led many of them there.

In the beginning, I walked around with well-known community members. Going in several times a week, often for the entire day, and showing my face was important. Some of the streets are pretty rough, but people, particularly the drug dealers, don’t seem worried anymore that I might be a cop or have ulterior motives. While working, I try to hold back and let folks approach me. I’ve been taking pictures on Skid Row long enough that I see familiar faces every time I return. It’s the first time working in America that I’ve felt such connection to a community—a place where no matter how broken someone may be, people do their best to take care of one another.

Watch the ABC7 news feature on the article.

WARNING: GRAPHIC IMAGERY BELOW